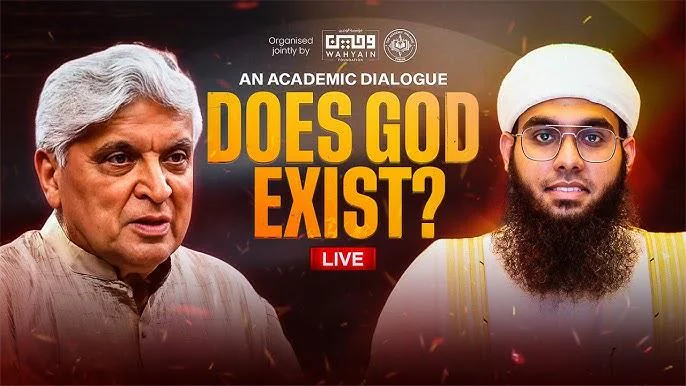

Nadwi vs. Akhtar on the Existence of God: What the Debate Reveals—and What It Cannot Decide

Public debates on questions like “Does God exist?” attract massive attention because they touch something deeply human: our search for meaning, justice, and truth. The recent debate between Mufti Shamail Nadwi and Javed Akhtar in New Delhi became widely discussed not because it answered this question, but because it exposed how differently people think, argue, and react when confronted with such fundamental issues.

To understand the value of this debate, we must look beyond who appeared confident or who received more applause, and instead examine what debates like this are actually good for, where they fail, and how they can be made more meaningful.

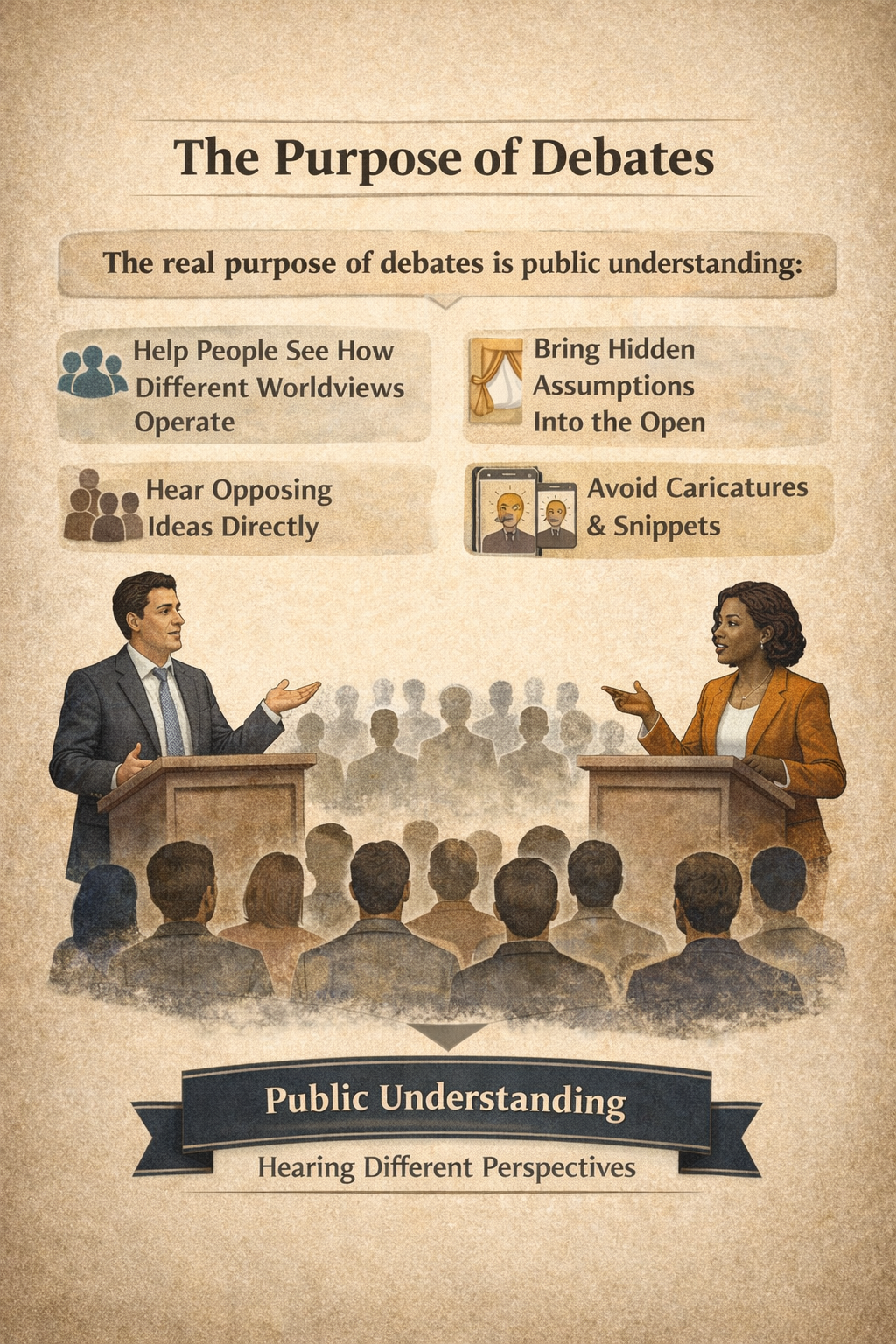

What Debates on God Are Really For

Debates about God are often misunderstood. They are not designed to deliver final answers or force one side to surrender. Questions about God, purpose, and existence have been discussed for thousands of years by philosophers, theologians, and scientists, and no single debate can resolve them.

The real purpose of such debates is public understanding. They help ordinary people see how different worldviews operate. They bring hidden assumptions into the open. They allow listeners to hear opposing ideas directly instead of through caricatures or social media snippets.

In the Nadwi–Akhtar debate, this function was clearly visible. Akhtar approached the question from a rational and human-centered perspective, demanding evidence and pointing to human suffering as a challenge to belief. Nadwi approached it from a philosophical and religious perspective, arguing that God is not something science is meant to test, and that questions of ultimate cause belong to a different category altogether. Even without agreement, the audience could see where the disagreement truly lay.

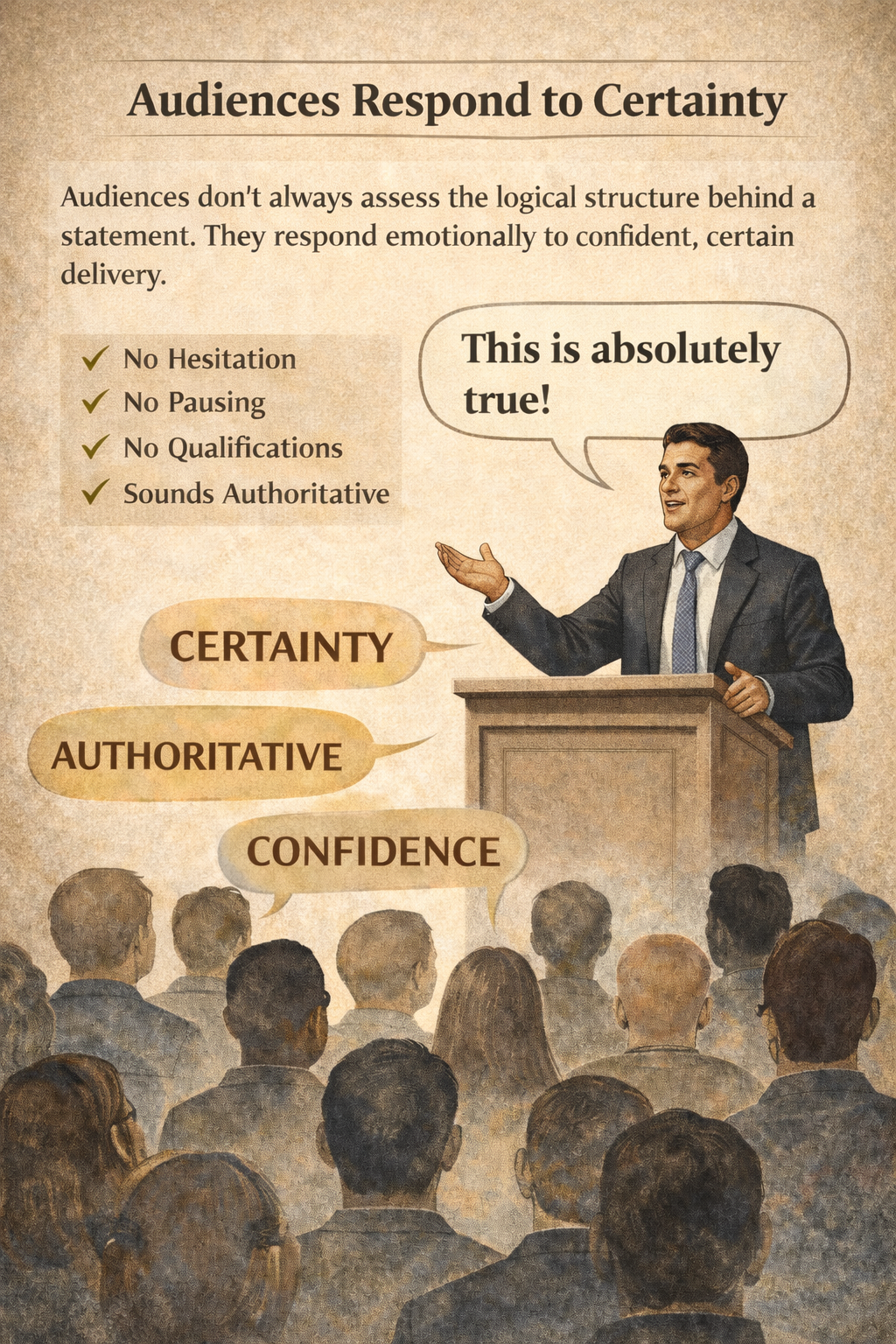

Why Confidence Often Beats Content in Public Debates

One of the most important lessons from this debate has nothing to do with theology and everything to do with human psychology. Audiences often judge debates not by the strength of arguments, but by the confidence with which those arguments are delivered.

This happens because following logic carefully is mentally exhausting. It requires attention, patience, and background knowledge. Confidence, on the other hand, is an easy shortcut for the brain. When someone speaks clearly, quickly, and without hesitation, our minds interpret that as authority. We assume that someone who sounds sure must know what they are talking about.

In the Nadwi–Akhtar debate, as in many others, this led to moments where style overshadowed substance.

Applause Versus Understanding

There were moments in the debate when strong applause erupted after bold statements. For example, when a speaker confidently declared that God is the ultimate foundation of all reality, the statement sounded powerful and complete. For believers, it felt affirming. For others, it sounded profound.

What many people reacted to was not the logical structure behind the claim, but the certainty with which it was delivered. The audience was not mentally walking through the philosophical reasoning step by step. They were responding to confidence. Because the speaker did not hesitate, pause, or qualify the statement, it felt authoritative.

This creates what can be called the “clap-worthy versus thought-provoking” trap. Statements that invite reflection often sound uncertain and careful, while statements that invite applause are bold and absolute. Unfortunately, truth is usually closer to the former than the latter.

Speed, Fluency, and the Illusion of Mastery

Another factor that shapes audience perception is speed. When a speaker talks quickly and presents many points in a short time, the audience often feels overwhelmed in a positive way. It creates the impression that the speaker knows far more than the opponent.

In debate culture, this is sometimes called overwhelming the opponent with information. If a speaker lists many scientific facts, philosophical terms, or historical references rapidly, most listeners do not have the ability to check their accuracy in real time. Instead, they think, “This person clearly knows what they’re talking about.”

In the Nadwi–Akhtar debate, both speakers at times delivered dense ideas quickly. For some viewers, this created admiration. For others, confusion. In both cases, confidence and fluency often mattered more than whether the audience truly understood the point being made.

Emotion as Moral Authority

Emotion plays a powerful role in debates, especially on topics like God and suffering. In the New Delhi debate, Javed Akhtar spoke passionately about the suffering of children in war zones. These moments were emotionally strong and morally serious.

Such arguments feel unchallengeable because they appeal to our deepest sense of justice and compassion. When someone speaks with visible moral outrage, questioning their argument can feel almost immoral. The audience may conclude that because the emotion is genuine and justified, the conclusion must also be correct.

However, while emotional arguments are important for ethical reflection, they do not automatically settle philosophical questions. Pointing to suffering raises serious challenges for belief, but it does not logically prove or disprove the existence of a creator. Still, because the emotion is powerful, confidence combined with moral passion often persuades more effectively than careful reasoning.

The Authority Effect of Complex Language

Another dynamic visible in the debate was the use of complex philosophical terms. When a speaker uses words like “infinite regress” or “metaphysical necessity” smoothly and without hesitation, audiences tend to assume expertise.

Even if listeners do not fully understand these terms, the speaker’s comfort with them creates an aura of authority. The logic is simple: if someone sounds like an expert, they must be one. This discourages questioning and encourages acceptance.

In reality, complex language is a tool, not proof. A calm explanation in simple words often reflects deeper understanding than confident jargon. But public debates rarely reward simplicity.

Why Our Brains Work This Way

Psychologists explain this phenomenon through mental shortcuts. When faced with complex arguments, people unconsciously ask easier questions instead. Instead of asking “Was the argument logically sound?”, they ask “Who sounded more confident?”, “Who stayed calm?”, or “Who had the last word?”

These shortcuts help us cope with complexity, but they also mislead us. In debates like Nadwi versus Akhtar, many people decided who “won” based on delivery rather than depth. This does not mean the audience is unintelligent. It means they are human.

Understanding the Difficult Words That Shaped the Debate

Much of the confusion around the debate came from unfamiliar terminology. For example, metaphysics refers to questions about existence and reality that cannot be tested physically. Nadwi relied on this idea to argue that God is not something science can measure.

Epistemology, though rarely named explicitly, was at the heart of the debate. It is the study of how we know what we know. Akhtar trusted scientific proof above all, while Nadwi argued that logical reasoning and philosophy also count as valid knowledge.

Infinite regress refers to an endless chain of causes with no beginning, like dominoes falling forever without a first push. Philosophers use this idea to argue that there must be a first cause to start everything.

Metaphysical necessity means something that must exist for reality to make sense at all, like a foundation is necessary for a building to stand. Nadwi used this idea to describe God.

Empiricism, which shaped Akhtar’s approach, is the belief that knowledge comes only from what we can observe or measure with our senses.

When these terms were used confidently, audiences often reacted emotionally rather than intellectually, cheering the speaker even when the meaning was not fully understood.

What the Debate Achieved—and What It Could Not

The Nadwi–Akhtar debate did not answer whether God exists. Expecting it to do so was unrealistic. What it did achieve was more subtle and more valuable. It showed how deeply our assumptions shape our conclusions. It demonstrated that disagreement does not require hostility. It encouraged millions to think about questions they usually avoid.

At the same time, it revealed the limits of debate as a tool. Without shared definitions and agreed standards of proof, debates risk becoming performances rather than explorations.

How Such Debates Can Be Made More Meaningful

For debates on God to be more successful, expectations must be clear. Organizers should emphasize that the goal is understanding, not victory. Speakers should explain ideas slowly and simply. Definitions should be clarified before arguments begin.

Most importantly, audiences should be encouraged to listen critically, not emotionally. Confidence should be admired, but not confused with correctness.

Is Debate the Best Way to Discuss God?

Debate has value, but it is not always the best method for this topic. Dialogues, long-form conversations, books, and personal reflection often allow deeper exploration without the pressure to win. Many people shape their beliefs about God through life experience rather than arguments.

Final Reflection

The Nadwi–Akhtar debate was not a failure because it lacked a conclusion. It was a mirror showing how humans argue, listen, and judge. It reminded us that confidence is persuasive, emotion is powerful, and truth is often complex and slow.

If debates like this teach us to listen more carefully, think more patiently, and judge less hastily, then they serve a purpose far greater than declaring a winner.