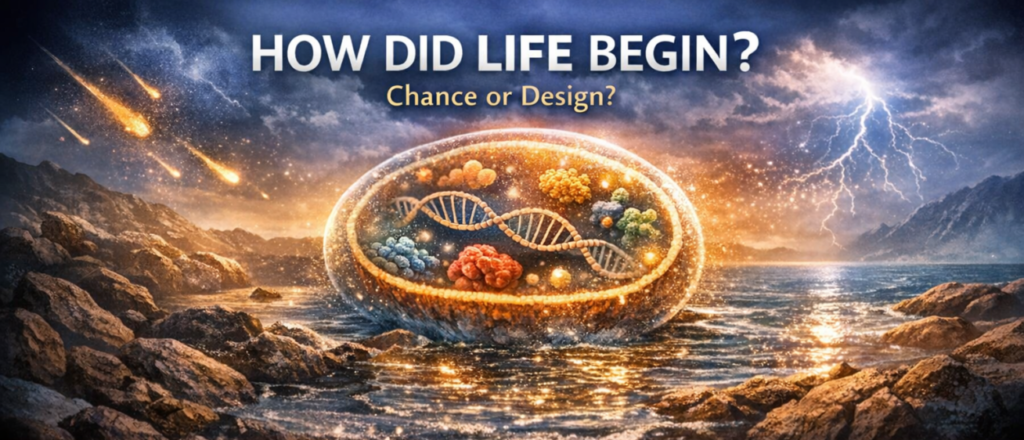

Series: ‘Beyond Evolution – Rethinking The Human Existence’

This article is part of a series that challenges the view of biological evolution as an unguided process. By examining biological systems that require simultaneous coordination and functional coherence, the series explores key examples where evolutionary explanations appear scientifically weak or logically insufficient—particularly in addressing the origins of life, biological complexity, and human uniqueness.

This article looks at the very beginning of life — the point before evolution could even start.

A Simple Analogy

Imagine walking along a beach and finding a smartphone lying in the sand. You could describe how later models of the phone became faster, slimmer, and more advanced, but that would not explain how the very first phone assembled itself out of sand and seawater. The problem is not small — it is foundational. Unless you can explain how the first phone came to be, the rest of the story is incomplete.

This is the same challenge faced when we ask: how did life itself begin?

The Question Before Evolution

Evolution is often presented as the explanation for life on Earth. However, evolution does not address the very beginning of life. It operates only after a living system already exists and is capable of reproduction and variation. Before natural selection can act, there must already be a functioning living cell. The most fundamental question, therefore, is not how life changes, but how life begins.

To approach this question, we must look at the basic building blocks of simplest living organisms known to science.

Understanding the Building Blocks of Life

Before discussing the origin of life, it is important to understand three basic terms that appear in every living cell: DNA, genes, and proteins. These are not abstract ideas. They are the physical and functional foundations of all biological life.

DNA is a long molecular structure that stores information. It acts like an instruction manual inside the cell. The information in DNA tells the cell how to grow, how to maintain itself, and how to reproduce. DNA itself does not perform actions. It stores coded instructions that must be read and carried out by other components of the cell.

A gene is a specific segment of DNA. Each gene contains instructions for a particular task. Many genes provide instructions for making proteins, while others control when these instructions are used or help maintain the system. Genes do not work alone. They operate as part of an organized network that coordinates the life of the cell.

Proteins are the molecules that actually perform work inside the cell. They build structures, speed up chemical reactions, transport materials, repair damage, and regulate processes. Almost everything that happens in a living organism happens because proteins are doing it. Without proteins, DNA instructions remain inactive and useless.

With these basic ideas in mind, we now examine the simplest organisms which might came into existence.

The Simplest Living Cells Are Still Highly Complex

One of the simplest known free-living organisms is Mycoplasma genitalium. It is often described as a minimal cell because it lacks many features found in other bacteria. Even so, it contains approximately 580,000 DNA base pairs and around 525 genes. From these genes, it produces roughly 400 to 450 proteins. It also possesses ribosomes, DNA replication machinery, RNA transcription systems, a protective membrane, energy-producing pathways, and repair mechanisms.

Another example is Pelagibacter ubique, one of the most abundant organisms in Earth’s oceans. This organism has about 1.3 million DNA base pairs and approximately 1,350 genes. It produces more than 1,300 proteins and maintains efficient metabolic and regulatory systems that allow it to survive in vast numbers.

A third example is Nanoarchaeum equitans, one of the smallest archaeal cells known. Although it depends on another organism for certain resources, it still contains nearly 490,000 DNA base pairs and more than 500 genes. It possesses ribosomes, genetic coding systems, protein synthesis machinery, and replication processes.

These organisms represent the lower boundary of life, not its complexity.

What Proteins Are and Why Life Depends on Them

Proteins are central to life. They are not uniform molecules, but highly specialized structures with precise shapes and functions. A protein is built from a chain of amino acids arranged in a specific order. This order determines how the protein folds into a three-dimensional shape. If the folding is incorrect, the protein often fails to function.

Within even the simplest cell, hundreds of different proteins must exist at the same time. Each protein must be present in the correct quantity and must interact properly with other proteins. Life depends not just on having proteins, but on having a coordinated system of proteins working together.

Genes Are Not Just Protein Instructions

Genes are often described as instructions for making proteins, but this is only partly true. A gene is a piece of DNA that holds information, but it cannot work by itself. The information must first be copied and used inside the cell.

RNA helps with this process. When a gene is needed, its information is copied into RNA. This RNA carries the message from DNA to the place where proteins are made. Some RNA molecules do not make proteins at all, but instead help the process run correctly.

Ribosomes are tiny machines inside the cell. They read the RNA message and use it to build proteins. Without ribosomes, proteins cannot be made, and without proteins, life cannot continue.

Some genes control when other genes are turned on or off and how much protein is produced. Other genes help repair damage. This shows that genes work as a system. Some store information, some pass it on, some build, and some control. Even the simplest cells depend on this organized network.

Interdependence Creates a Fundamental Problem

All of these systems depend on one another. DNA stores instructions, but it cannot act without proteins. Proteins cannot be made without ribosomes. Ribosomes require RNA and proteins to exist. Energy must be continuously supplied to keep the system active, and a membrane must enclose everything to prevent destruction.

None of these components can function independently. They must appear together, coordinated from the start. This circular dependency poses a serious challenge for explanations based on unguided processes.

Scientific Attempts

Scientists have suggested different ideas to bridge this gap. Some say the early oceans were like a “primordial soup,” rich in chemicals that somehow joined together into life. But chance cannot realistically assemble the complexity of a living cell. Others suggest an “RNA World,” where simple molecules began copying themselves, but these molecules are fragile and fall apart quickly. Still others propose that life arrived from outer space, through comets or meteors. But this only shifts the question: where did life begin in the first place?

Each attempt highlights the same truth: the first step of life remains unexplained.

Why This Matters

If the origin of life cannot be explained, evolution has no starting point. It can only describe changes in life after it exists; it cannot tell us how life began. That missing first step is not a minor detail — it is the foundation of the entire story. Without it, the chain of evolution hangs in midair, unsupported.

The Assumption of Self-Assembly

Let us assume that life assembled itself without any guiding intelligence. Even under this assumption, the problem remains one of organization rather than existence. Hundreds of genes must be present simultaneously. Hundreds of proteins must be produced in correct proportions. Timing, balance, and stability must be maintained from the beginning.

Random chemical reactions do not coordinate systems. They do not plan future usefulness. They produce disorder, not integrated machinery.

Statistical and Organizational Limits

Functional proteins make up only a tiny fraction of all the possible amino-acid sequences that could exist. Most random sequences do nothing useful at all. Scientific studies have shown that the probability of a random chain of amino acids folding into a stable, functional protein is extraordinarily low—often estimated as less than one chance in trillions. In other words, if amino acids were joined together at random, almost every resulting protein would be useless or even harmful.

A living cell, however, does not rely on just one protein. It requires hundreds, often thousands, of different functional proteins, each with a specific shape and role, all present at the same time. These proteins must also work in coordination, be produced in the correct amounts, interact accurately with other molecules, and be protected by error-correction systems. When coordination, regulation, and quality control are added to the requirement, the challenge increases exponentially, making the idea of such a system forming by chance increasingly difficult to explain.

The difficulty is not merely statistical. It is organizational.

Why Coordination Points to Design

Chemistry explains reactions, but it does not explain coordinated systems that depend on precise arrangement. To bring genes and proteins together into a functioning cell requires selection, timing, and integration. Even if all components existed, something must account for their organized assembly.

This is why design becomes a rational inference. Design, in this context, means intentional arrangement toward function.

The Final Question About DNA

This reasoning leads to a final question. If DNA is not itself a living structure, then what gives rise to life? DNA stores information, but it does not think, act, or choose. Yet no living cell can exist without it or without an equivalent information system.

If DNA itself requires organization and coordination, what produced DNA? And if DNA is not the starting point, what else could be?

Until these questions are answered, the origin of life remains unresolved.

Stay with us as we continue to examine the weaknesses of the evolutionary model and search for a deeper explanation of human existence.